Short term plasticity, spikes, and sparseness

- 9 minsReally excited to see this new preprint, Short-term synaptic plasticity makes neurons sensitive to the distribution of presynaptic population firing rates by Luiz Tauffer and Arvind Kumar up on bioRxiv today. They’re exploring an idea that I was playing with a lot during my PhD - the notion that short-term plasticity (STP) of synaptic inputs can make neurons sensitive to how spikes are distributed among their inputs. I was messing with modeling this myself, and even did a few experiments, but ran out of time to turn it into something before I graduated. But I’ve always thought that it was a really powerful idea, and I’m really satisfied to see people working through it more fully and putting it into a strong mathematical framework.

What is the best way to distribute spikes?

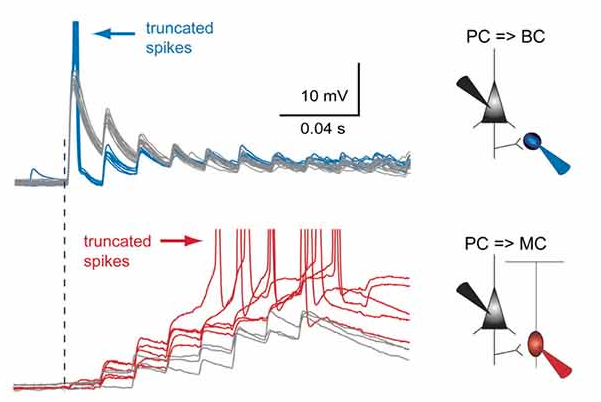

I initially started thinking about this in the context of excitatory (E) inputs onto somatostatin (SST) and parvalbumin (PV) expressing interneurons in the neocortex. Short-term plasticity at these synapses is very different. E-to-PV synapses are strongly depressing, whereas E-to-SST synapses are strongly facilitating. There’s a really nice example of this in Silberberg & Markram 2007 - see just below. The top traces shows the depressing EPSPs in a PV+ basket cell in response to a 70 Hz train of 10 spikes in a connected pyramidal cell (PC, spikes not shown), while the bottom traces show the facilitating EPSPs in a SST+ Martinotti cell in response to the same stimulus.

You can see in the red traces in the bottom row that while the first spike from the pyramidal cell typically fails to evoke any EPSP (due to the low basal probability of release at this synapse), yet a rapid burst of spikes in a single pyramidal cell is often enough to drive the SST+ Martinotti cell to fire. This is a really striking phenomenon (which, it’s worth noting, was also concurrently discovered by another group). It appears to rely heavily on the facilitating nature of the E-to-SST synapse - in spite of the example given in the top/blue traces, a single pyramidal cell is almost never capable of driving a PV+ cell to fire (in the quiescent conditions seen in a slice prep).

STP occurs essentially independently at different synapses, meaning that the spikes all need to be in the same presynaptic cell in order to drive facilitation. If you had put 1 spike each into 10 different PCs that all connected onto an SST+ cell (instead of 10 spikes into 1 PC), you would expect to get a very different outcome: probably there would be very little depolarization at all, since there would likely be failure to release glutamate at most of the synapses.

Early in grad school I started thinking of this as a sort of puzzle - if you have a given number of spikes to put into a population of neurons, is there an optimal way to distribute them such that you’ll maximally drive a downstream neuron? Does the answer depend on the short-term plasticity properties of the input synapses?

Intuitively, you might expect that the answer would be very different if the inputs onto a neuron were strongly depressing (as is the case for PV cells) - there, you might want to do something like distribute spikes as evenly as possible, in order to minimize the amount of depression that occurs.

To get at this question, I started doing some experiments where I recorded from PV and SST cells in cortical slices while using a digital micromirror device to try to optogenetically create different distributions of activity in the excitatory population that provided inputs to these cells. For various reasons, I didn’t have time to finish the project, but the data looked promising. I was also pretty confident that, if you accept the (very robust) results showing that excitatory inputs to PV and SST cells have different short-term plasticity, then the optimal way to distribute spikes among an input population must be different - that this was a consequence that could be deduced if you had a good understanding of the short-term plasticity itself. I started playing around with trying to model this myself, which produced some interesting stuff too. But I never really managed to get things to come together into a story.

‘Short-term synaptic plasticity makes neurons sensitive to the distribution of presynaptic population firing rates’

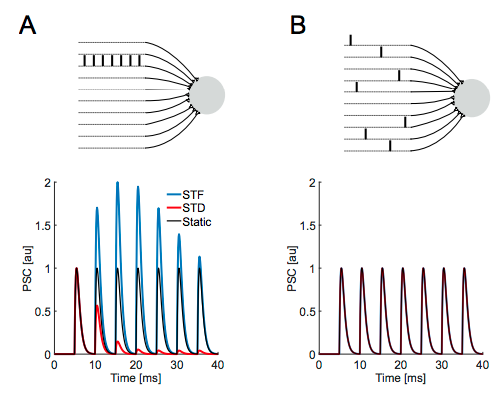

Luckily for me, Tauffer & Kumar have done a really nice theoretical study looking at exactly this thing. These panels from their first figure show the exact intuition I was describing above - short term facilitation/depression take place in panel A, where you have 7 spikes concentrated in 1 presynaptic input, but do not occur in panel B where you have 7 spikes coming from 7 inputs.

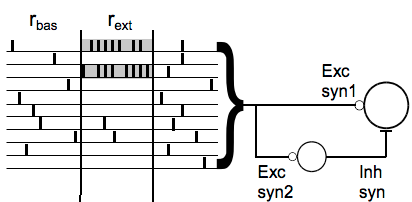

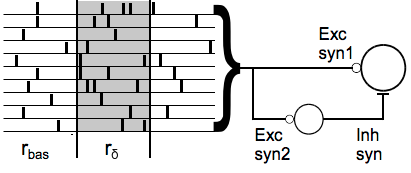

For most of the rest of the paper, they consider the more realistic scenario where you have a population of $N$ inputs operating as heterogeneous Poisson processes, where they all start out firing spikes with a baseline rate $r_{bas}$, but then increase their firing by some amount $R_{ext}$ to simulate an external stimulus. The additional activity $R_{ext}$ is distributed among $N_{ext}$ of the $N$ input neurons. In the case where $N_{ext} < N$, the extra activity is ‘sparse’ i.e. it is concentrated in a subset of the total population and each of these $N_{ext}$ neurons increases their activity by $r_{ext} = R_{ext}/N_{ext}$.

In the case where $N_{ext} = N$, the extra activity is densely distributed, meaning all the input neurons increase their activity by the uniform amount $r_{\delta} = R_{ext} / N$.

For a given choice of $R_{ext}$ and $N_{ext}$, the firing rates of every neuron in the input population are thus set to one of two discrete values during the stimulus - each neuron either starts firing at the increased rate, or they continue to fire at the baseline rate. This is a fairly simple way to think about distributing activity in a population, but it’s a good place to start.

Modeling short-term plasticity (STP) at the synapse

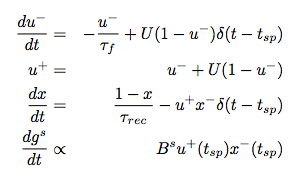

To model short-term synaptic dynamics, they use the classic Tsodyks-Markram equations.

There’s an excellent Scholarpedia article on how these work. The basic idea is that each synapse has two internal variables that control its dynamics: $x$, which represents the fraction of total synaptic resources available and is expended every time there is a presynaptic spike; and $u$, which controls how much of the remaining $x$ is expended per spike. $x$ gradually replenishes over time, but can be depleted by extended high frequency spiking; in physiological terms, this can roughly be thought of as modeling the depletion of readily releasable vesicles at the synapse. Conversely, $u$ decays toward 0 between spikes, but can build up during high frequency spiking, roughly corresponding to the accumulation of calcium in the presynaptic terminal and corresponding increase in probability of release.

Put other stuff here

The effects of rate and sparseness on synaptic efficacy

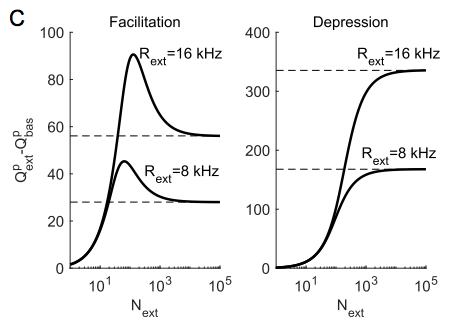

This panel illustrates one of the key ideas here. The quantity on the y-axis is the amount of extra synaptic resources being released (this is, I think, directly proportional to the extra postsynaptic conductance that would be evoked if you assume for simplicity that the decay timeconstant of this conductance is very small) when the total firing rate of the input population is increased by either 8k or 16k spikes per second. The x-axis shows how many of the $N = 10,000$ presynaptic neurons these extra spikes are distributed among - so on the left side, a small number of neurons increased their firing a lot and on the right side the entire population of neurons increased their firing rate by 0.8 or 1.6 Hz. The curve for depressing synapses is monotonic and saturating - the more you distribute the spikes, the more efficiently you use them. But the curves for the facilitating synapse are not the same - these show a peak in the middle, meaning you are most efficient if you distribute your spikes among a smaller subset of the total population.

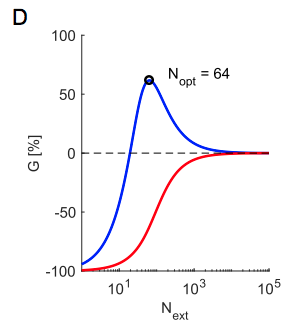

This is the crucial takeaway so let’s drive it home - in panel D below, the blue line is a facilitating synapse and red is a depressing one. The y-axis shows the same quantity as in panel C, this time normalized to show percent change from the furthest right point on the curve (e.g. spikes are spread densely among all neurons). For the facilitating synapse, you get >50% more bang for your buck downstream if you concentrate your spikes in $N_{ext} = 64$ neurons compared to the dense distribution.

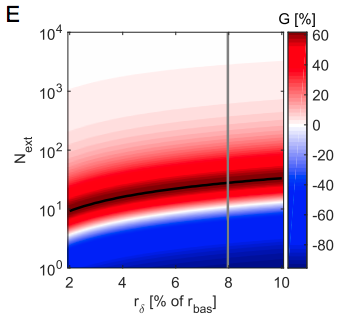

The optimal number of neurons in which to concentrate your spikes is linearly related to the size of the increase in firing rate $r_{\delta}$ relative to the baseline firing rate $r_{bas}$ - see the black line in panel E (note that it looks curved due to the log scale)

Of course, these solutions only apply to two specific sets of parameters for the Tsodyks-Markram model. The authors go on to explore how varying the short-term plasticity properties affects the gain surface of synaptic efficacy. I won’t go into it too much here, but tuning these properties changes what the optimal distribution pretty much how you might expect - making synapses more strongly facilitating or depressing than the two examples they start with exaggerates the differences in what the optimal distributions look like.

More complicated distributions of presynaptic activity

Impact on feedforward inhibition motifs

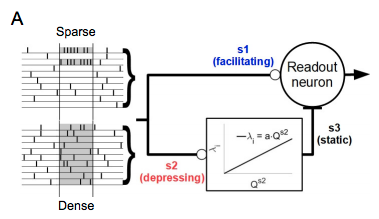

Tauffer & Kumar go on to ask how this phenomenon might impact transmission in a simple feedforward inhibition (FFI) motif where the synapses onto the excitatory neuron are facilitating, and the synapses onto the inhibitory neuron are depressing.